The work of Tim Cason and his colleagues in the Vernon Smith Experimental Economics Laboratory (VSEEL) is helping policymakers create regulations that give firms incentives to undertake new ways of controlling pollution and environmental sustainability. (Stock image)

The work of Tim Cason and his colleagues in the Vernon Smith Experimental Economics Laboratory (VSEEL) is helping policymakers create regulations that give firms incentives to undertake new ways of controlling pollution and environmental sustainability. (Stock image)

Investing in the Environment

Giant leaps to a sustainable economy and planet

Countries across the globe now use emissions trading systems to reduce pollution more cost-effectively. But what incentives do these tradable-permit markets offer companies to invest in advanced pollution abatement technology?

Purdue’s Tim Cason, the Gadomski Chair of Economics and director of the Vernon Smith Experimental Economics Laboratory (VSEEL) at the Krannert School, is addressing that question through experimental economics. He most recently investigated the topic in a paper co-authored with United Kingdom colleague Frans de Vries from the University of Stirling that is forthcoming in Environmental and Resource Economics.

In “Dynamic Efficiency in Experimental Emissions Trading Markets with Investment Uncertainty,” the researchers used a lab experiment to assess how two methods of allocating tradable permits — auctioning or grandfathering them — might influence businesses’ decisions about making new technology investments to reduce pollution.

In “Dynamic Efficiency in Experimental Emissions Trading Markets with Investment Uncertainty,” the researchers used a lab experiment to assess how two methods of allocating tradable permits — auctioning or grandfathering them — might influence businesses’ decisions about making new technology investments to reduce pollution.

“Like a carbon tax, these trading systems are another way of putting a price on emitting pollution,” Cason says. “Among the things they do is provide incentives for firms to develop innovative, lower-cost methods of generating electricity or removing pollution. Similarly, this new set of experiments examines how specific details of these markets’ design will influence them to undertake the research and development needed to make those innovations.”

Although the U.S. government implemented emissions trading policies to reduce acid rain in the 1990s, Congress has not adopted trading systems for greenhouse gas emissions. But Cason says they are common in Europe and other international markets as well as in individual states, including California and those on the East Coast.

“The idea behind emissions trading is that individual firms are provided the right to emit a certain amount of pollution, such as an electric power utility releasing carbon emissions. It’s when these emissions are tradable that the market comes into play,” he says. “If these firms find a less expensive way of reducing pollution compared to others, they can make those reductions themselves and sell their excess permits to firms who are having more difficulty reducing emissions or facing higher costs.”

Spurring Innovation

According to Cason, most economists favor emissions trading and pollution taxes because they equalize the marginal pollution-control cost across firms and limit emissions less expensively than mandatory constraints. His research with de Vries specifically examines the two most common types of permit allocations for emissions trading — grandfathering and auctioning.

“In the European Union, for example, firms that polluted in the past were typically ‘grandfathered’ in to receive the permits for free,” Cason says. “But it’s transitioning to a system where the permits are auctioned off, which provides revenue for the government.”

The study’s findings also extend beyond experimental economics into behavioral economics, particularly with regard to how people treat opportunity costs.

“In theory, people should treat opportunity costs just like regular costs, but that doesn’t seem to apply to emissions trading,” he says. “Firms that receive emission permits for free through grandfathering consider them an implicit opportunity cost and trade them differently than permits that are purchased at auction with an explicit cost.”

Ultimately, the research indicates, although both types of permit allocation lead to significant investment, auctioning provides stronger research and development incentives to invest in pollution abatement technology than grandfathering. That’s a key takeaway for Cason.

“One of the most important features of environmental regulation is how much it spurs innovation,” he says. “We want to create regulations that give firms the incentives to undertake new ways of controlling pollution.”

Nobel Traditions

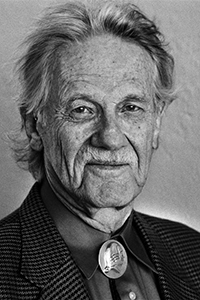

Cason takes pride in building on a tradition of groundbreaking research begun by the namesake of the Vernon Smith Experimental Economics Laboratory, a Nobel Prize-winning economist who taught at the School of Management for 12 years.

Smith, who is widely recognized as the “father of experimental economics,” began his academic career and research at Purdue in 1955. Borrowing techniques from lab experiments in psychology, he created the first “classroom” markets by designating half his class as buyers and half as sellers of fictitious goods. He gave the buyers and sellers different ranges of prices and had the students interact freely and negotiate trades until price and quantity achieved equilibrium, or in economic terms, “made a market.”

Smith, who is widely recognized as the “father of experimental economics,” began his academic career and research at Purdue in 1955. Borrowing techniques from lab experiments in psychology, he created the first “classroom” markets by designating half his class as buyers and half as sellers of fictitious goods. He gave the buyers and sellers different ranges of prices and had the students interact freely and negotiate trades until price and quantity achieved equilibrium, or in economic terms, “made a market.”

Cason met Smith, his mentor, while working as a visiting graduate student at the University of Arizona in 1989, the same year Purdue awarded Smith an honorary doctorate in management. The colleagues reunited in 2002 when Smith shared the Nobel Prize in Economics and spent part of the year in West Lafayette as a visiting professor.

The lab that formed around Smith’s pioneering work was renamed in his honor in 2003. Today, Cason and other Krannert researchers expand on his legacy through experiments that

test increasingly complex and sophisticated economic hypotheses and mechanisms before their introduction to real markets.

Smith, who continues to teach and research, has also made seminal contributions to production theory, public choice, environmental economics, and behavioral economics. He has been foundational in the emerging field of neuroeconomics.

Smith most recently returned to Purdue in June to share his work with students from 20 different universities at an International Foundation for Research in Experimental Economics (IFREE) workshop hosted by the Krannert School. Smith founded IFREE in 1997 to support research and education in the field, and continues to serve as the foundation’s president.

“IFREE incubates creative market and personal exchange system projects that extend the boundaries of economic research and nurture thinking outside the traditional economics research, education and policy boxes,” Smith says. “It offers a way of thinking about getting things done, and it is a source of inspiration that moves people to want to contribute and make things happen.”

The workshop at Krannert provided advanced undergraduates (juniors and seniors) with an introduction to experimental methods in economics. Each module included an experiment in VSEEL and a discussion of how such experiments inform research developments in behavioral economics and policy.

Several faculty members from the Department of Economics at Purdue participated in the workshop, including Evan Calford, David Gill, Victoria Prowse, Yaroslav Rosokha and Cathy Zhang. The spotlight shined most brightly on Smith, however, who at age 91 remains an invigorating presence in the classroom.

“Vernon showed the students some data he collected at Purdue in 1956 in one of the first economic experiments ever conducted,” Cason says. “It’s always great to have him back at Krannert.”